What effect did the coronavirus pandemic have on our food supply?

From supermarket shortages to the hospitality sector shutdown, we look at how COVID-19 impacted food supply in the UK.

The coronavirus pandemic disrupted the entire UK food supply system.

We rely on a complex international network of highly efficient supply chains to help put food on our plates.

But due to measures to control coronavirus, supermarkets ran out of essential food supplies, food banks found they had almost double the demand compared to 2019, suppliers to restaurants, pubs and cafes came upon financial hardship, and key workers in the food sector had to risk their health to keep the nation fed.

Future disruptions to our food supply are possible. Further waves of coronavirus, or the effects of climate change could have disastrous effects on our ability to access enough healthy food. We need to know how to approach these future scenarios.

This is why we, MPs on the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Committee, launched an inquiry into COVID-19 and food supply in April 2020. With two further lockdowns in 2020, the supply of food was once again affected. In January 2021, we launched a follow-up inquiry, monitoring what had and had not changed since our July 2020 report.

What happened?

We received over 150 written submissions and heard from businesses in the food supply chain, food aid organisations, charities, academics and the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) throughout April, May and June 2020. When we reopened the inquiry the following January and February, 49 of those organisations sent us updated evidence.

We received thousands of responses when we asked you to tell us your experiences and views in an online survey.

1. We received over 5,500 responses to our survey on food supply during Covid-19. Thanks to everyone who took part. Here’s what you told us (thread):

— EFRA Committee (@CommonsEFRA) May 14, 2020

We heard from people living in urban and rural areas across the UK, in households ranging from a single person to multiple families under one roof. We heard from people who were shielding and receiving food parcels, people trying to access support from food banks, and others who shopped in much the same way as they did before the pandemic.

In February 2021, we held two further sessions on food supply, inviting many of the same people back to tell us about their experiences over the previous six months.

Here is what we heard.

3 key ways the pandemic impacted access to food

1. There was a lack of clarity about how much food people needed to buy.

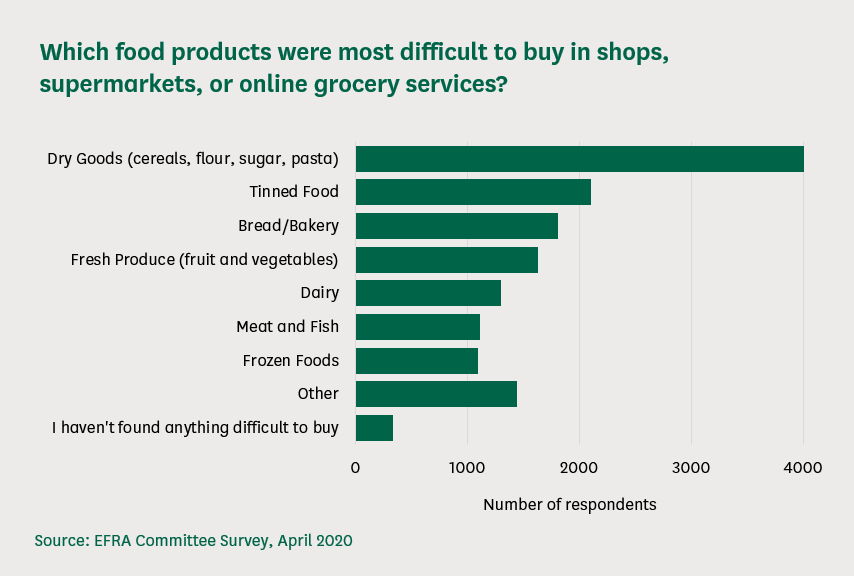

With people preparing for lockdown, possible self-isolation and the shift to eating all meals at home, demand for groceries soared in March, amounting to the biggest month of grocery sales ever recorded in the country. As a result, many shoppers encountered empty shelves, particularly when looking for dry and tinned goods.

The Government worked well with supermarkets and food retailers once the pandemic hit the UK, relaxing competition laws so that companies could work together, co-ordinate opening hours, and share delivery vans.

However, there was much confusion over how much food people actually needed to have in their homes. The Government told people to stop eating out and stay at home while closing schools, but they also told the public to limit the amount they bought in supermarkets.

"I don’t think there was any helpful guidance in respect of the likely effect of the lockdown on food supplies. There was a sudden flurry of news reports about people buying loo roll and pasta like it was going out of fashion, which scared us."

The Government encouraged people who were asked to shield to rely on supermarket online delivery services or friends or family, in place of the national food parcels provided in the first lockdown. In our follow-up inquiry, we heard that this potentially excluded people who could not afford supermarket minimum spends or delivery charges or found it harder to access the internet.

2. The pandemic made more people unable to afford food.

Food banks and food aid providers began reporting shortages in their stock in early March 2020. During the first few weeks of the crisis these organisations, much like consumers, found it difficult to buy the food they needed because of lack of supply and rationing from supermarkets.

At the same time, demand grew in leaps and bounds. We heard from the Trussell Trust that "there was an 81% increase in demand and, quite alarmingly, a 122% increase in the number of children receiving food through [their] food banks", compared to the same period of time in 2019. It is estimated that 5.9 million adults in the UK experienced food poverty from August 2020 to February 2021.

The Government designed a system to provide children with a substitute for free school meals after schools closed, but many had difficulty taking advantage of it because it didn't include convenience stores and discount retailers from the start.

In the third national lockdown beginning in January 2021, the Government took a 'food parcel first' approach to distributing free school meals to pupils not attending school. However, it later reintroduced a national voucher scheme after serious concerns were raised about the standard of some parcels.

There are millions of people whose ability to afford sufficient, nutritious food has been severely disrupted or worsened. This situation may get worse as the economic impacts of the pandemic continue to unfold.

3. Foodservice and hospitality businesses and their suppliers are going to feel the effects of lockdown for years.

As pubs, bars and restaurants shut down, the companies and workers who supplied them found their revenue source removed overnight.

Those effects reached British agriculture. We learned that farms tried to move food originally destined for hospitality to supermarkets or to food aid organisations, but the adjustment was difficult. British dairy farmers, for example, lost over £41 million by July 2020.

"All our fish and chip shops shut overnight, so those who process potatoes that would normally go into that market have been massively challenged."

The hospitality sector and its suppliers have seen revenues decline by over £72 billion over the pandemic. Suppliers for the hospitality sector have not received the same level of support as those they supply, and urgently need help in order to reduce the risk of the supply chain collapsing.

Our key recommendations to

fix the problem

1.Ensuring people can afford enough healthy food is the responsibility of multiple Government departments. Ministers have mobilised their departments to support vulnerable people to access food during the pandemic. This needs to continue as the UK recovers. To bring that work together, the Government should appoint a Minister for Food Security who is empowered to draw together policy across departments on food supply, nutrition and welfare. It should also consult on a legal 'right to food'.

2.The Government should work with producers, processors and wholesalers servicing the hospitality and foodservice sector to monitor the health of food and drink suppliers as supply chains restart. It should urgently assess the impact of the closures to the hospitality sector on its suppliers and provide additional financial support to them during the period of reopening in 2021.

3.If another lockdown happens, the Government should ensure that families of children who would normally receive free school meals continue to be able to feed their children. Schools should have multiple options for providing free school meals and be able to choose the best one to meet their pupils' needs. It is unfortunate that the failings of some suppliers, in terms of quality and value, led to a fall in public confidence in England because parcels are the best option in some circumstances. The sector and the Government must learn from these failings and ensure that any future offering is consistently up to standard.

4.The Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) should continue to provide funding to charities to redistribute surplus food from farms and across the supply chain to frontline food aid providers for a further two years. This would help those who struggle to afford food as the effects of the pandemic continue, and reduce food waste from farms.

5.Food supply to supermarkets continued because we were able to keep food coming into the country. Future crises could stop this flow and cause more serious problems. The Government has to update its food resilience plans, taking into account how consumer behaviour can disrupt food supply and whether our efficient "just-in-time" supply chains are as resilient as they need to be.

We would like to put on record our unreserved thanks to all the key workers in the food supply chain whose efforts and sacrifices have meant that the nation is being fed during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Government must now respond to our report.

Our follow-up report, 'Covid-19 and the issues of security in food supply', was published on 7 April 2021. The Government has two months to respond to our report.

Our original report, 'COVID-19 and food supply' was published on 30 July 2020. The Government responded to our original report on 10 October 2020. You can read their response on our website. Detailed information on our inquiry into COVID-19 and the food supply can be found on our website.

If you’re interested in our work, you can find our more on the House of Commons Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Committee website. You can also follow our work on Twitter.

Looking at issues from the air we breathe to the food on our plates, Parliament’s Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Committee (EFRA) exists to scrutinise the administration, spending and policy of the Government’s Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs.

Cover image by Lum3n via Pexels