The future of Scotland's universities

How can we tackle the challenges and maximise the opportunities facing Scottish universities?

Our inquiry into universities in Scotland came during a period of intense pressure for the sector.

Education, including higher education, is devolved to Scotland. There are 19 universities and in the 2017–18 academic year, there were 230,940 students studying in Scottish universities.

Now Scotland’s universities face a “perfect storm” as long-term financial challenges have combined with the effects of covid-19 and Brexit.

Typically, the higher education sector in Scotland survives on a combination of international student fees, research grants and funding from the UK and Scottish Governments.

The pandemic has necessitated significant interventions by both the UK and Scottish Governments in order to support research, institutions and students. However, questions remain over whether it will be enough.

Our full report examines the challenges and opportunities faced by Scottish universities (and their students and research arms) as the sector adjusts to the pandemic and life outside the EU. It also assesses what further action is needed by the UK and Scottish Governments.

Here are five key recommendations we have identified in our report.

Five key recommendations to the UK Government

1. International student exchange

We note with regret that the Turing Scheme (the UK’s replacement for the EU Erasmus+ scheme) will not – as currently envisaged – support inward placements to the UK. Inward placements support the cultural education and experience of UK students as well as provide income sources to universities and local economies.

Subject to positive year-one results from the Turing Scheme, we recommend not only that the scheme continue with at least the same level of funding in future years, but that it be expanded to incorporate the funding of international students and academic staff placements to the UK.

2. Scottish presence within UK Research and Innovation (UKRI)

The academic outputs of Scottish universities will not only support our economic recovery following the pandemic but also bolster the UK’s standing in the world as we forge new post-Brexit international relationships.

Scottish institutions should be given greater prominence and influence within UKRI decision-making structures.

That should include a seat on the UKRI Board (as is already the case for some English institutions) and a seat on the UKRI Executive Committee (in the same way that Research England are represented).

3. UK spending on research and development

In the UK Government’s Research and Development Roadmap it made a commitment to reach 2.4% of GDP spend in this area.

UKRI have announced that the temporary reduction in UK overseas aid spending (ODA) in response to the pandemic will have a “significant impact” on the work they fund under ODA programmes.

The UK Government should ensure that the commitments it made in its UK Research and Development Roadmap are not derailed as a result of the temporary reduction in overseas aid spending.

4. Welcoming EU nationals

The UK Government should launch a new or expanded scholarship scheme to encourage the most talented EU students to study in the UK and Scotland.

This would help heal UK-EU divides following Brexit, assist in combating falling EU student numbers in Scotland and provide a new pathway to attract and retain the brightest and best from the EU.

The UK Government should also increase funding to Study UK in order to increase their capacity to target EU students who may be hesitant to study in the UK.

We also heard during our inquiry that academics from the EU working in Scotland have been returning to the EU, and that job applications from EU academics are being withdrawn.

We have been told that this not because they are not allowed to stay or come to Scotland. It is because they do not feel welcome following Brexit.

The UK Government must promote a positive narrative that, whilst we have left the EU, the UK and Scotland remain an attractive place to work for EU nationals, and the brightest and best the EU has to offer are not just ‘allowed’ to work here, but are actively welcomed.

5. Acknowledging the impact of reserved UK policies on Scottish higher education

Although higher education is a devolved competence, reserved UK Government policies – such as on foreign affairs, immigration and research and development – have significant consequences for Scottish universities.

The UK Government should continue to work with the Scottish Government (as well as the other devolved administrations) and acknowledge that higher education cuts across the competencies of all UK governments.

It should also outline how the Governments will work together to better deliver higher education in Scotland, for example through the tripartite meeting.

What happens now?

We have made these recommendations to the Government.

The Government now has two months to respond to our report.

Our report, 'Universities and Scotland', was published on 28 May 2021.

Detailed information from our inquiry can be found on our website.

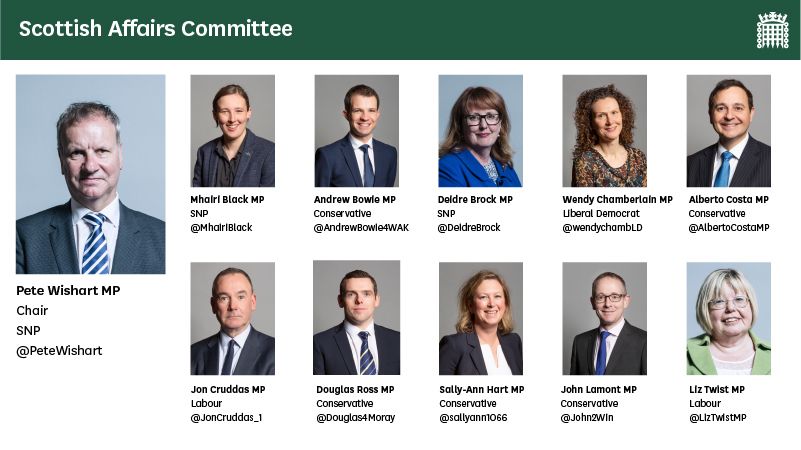

If you’re interested in our work, you can find out more on the House of Commons Scottish Affairs Committee website. You can also follow our work on Twitter.

The Scottish Affairs Committee works together to scrutinise the expenditure, administration and policies of the Scotland Office, and its associated bodies. We also examine the wider UK Government, to assess policies and legislation that lead to direct impacts on Scotland.

Cover image: Bonnie Hall EdD via Pixabay